Zimbabwe is currently in an economic crisis. According to the CIA World Factbook, inflation in the private sector rages well above 100,000%. The country is suffering from a -6% growth rate, 80% unemployment, and 68% of the population is below the poverty line. “Botswana built electric fences and South Africa has placed military along the border to stem the flow of thousands of Zimbabweans fleeing to find work and escape political persecution (CIA World Factbook).” How did Zimbabweans find themselves in this mess?

Robert Mugabe has been the president of Zimbabwe since it declared independence from Great Britain in 1980. Under his leadership, Mugabe has turned the country into the poster child for political and economic upheaval. Beginning in 2002, Mugabe forced thousands of white farmers off their land and gave the farms to his party leaders and cronies. Unfortunately, the new land lords were uneducated in farming. The resulting crop failures lead to severe food shortages. This seizure of land is only one example of the president’s property and human rights violations. Beyond this, Mugabe continues to print more money to pay off the national debt which only fans the flame of inflation. In spite of the economic turmoil, Mugabe has held his position of power through government-backed violence and rigged election.

In his book Power and Prosperity, Mancur Olson outlines his research on the conditions required for a nation to be prosperous. Among his major themes is the idea that economic prosperity is nearly impossible in the presence of corruption, government predation, and lack of private property rights. Clearly, Zimbabwe’s President Mugabe blatantly practices corruption, government-backed violence and predation, and disregards all private property rights. Is it any wonder that Zimbabwe is in such dire economic straits?

This is a CU Colorado Springs student blog for the following courses: Economic Freedom, and Power & Prosperity.

Wednesday, April 30, 2008

The Incentives of War

Olson offers powerful insights on why it is sometimes necessary to go to war in order to exhibit our military might – for that exhibition of strength and military dominance may help to keep others in line. We must occasionally prove that we can “organize the greatest capacity for violence” in order to maintain our status as a world superpower (11). I can appreciate the fact that we must carry a “big stick” so that others will not pick on us, but I question whether or not it is truly necessary for us to spend almost as much as the rest of the world combined to protect our nation. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, in 2005 “the USA was responsible for 48 percent of the world total” military expenditures, and was “distantly followed by the UK, France, Japan and China with 4–5 percent each”. This leads me to believe that there may be something wrong with the financial incentives that are built into the system. http://yearbook2006.sipri.org/chap8/chap8

After reading Olson I have a greater understanding as to why we go to war even when it seems that there is more opposition to war than support. His Logic of Collective Action provides powerful insights into this issue. The forces that advocate going to war are much stronger and well organized than those who oppose the war, and they certainly have a lot to gain individually since the multi-billion dollar defense contracts are spread over such a small number of corporations. Professor Eubanks is always pointing out that it all boils down to incentives, and the incentives for these multi-billion corporations are certainly stacked in favor of war. In the 2005 documentary “Why We Fight,” Chalmers Johnson points out “the defense budget is ¾ of a trillion dollars. When war becomes that profitable you are going to see more of it.” War certainly has been extremely profitable for a few, and those few sure seem to carry a lot of weight in Washington. http://www.sonyclassics.com/whywefight/

I believe the excessive expenditure of our taxpayer dollars is due to major flaws with the incentive system. These corporations have little to gain in times of peace, especially if there is no perceived threat to our national security. The vast majority of us find peace to be more profitable than war (in the form of lower taxes), but unfortunately this is not the case for the defense contractors who have greater profits to gain in times of war and therefore, more incentives to promote war. Until we solve the incentive issue it seems likely that a small segment of the population will advocate war even if is it not in the best interest of our country…and you and I will end up paying for it.

After reading Olson I have a greater understanding as to why we go to war even when it seems that there is more opposition to war than support. His Logic of Collective Action provides powerful insights into this issue. The forces that advocate going to war are much stronger and well organized than those who oppose the war, and they certainly have a lot to gain individually since the multi-billion dollar defense contracts are spread over such a small number of corporations. Professor Eubanks is always pointing out that it all boils down to incentives, and the incentives for these multi-billion corporations are certainly stacked in favor of war. In the 2005 documentary “Why We Fight,” Chalmers Johnson points out “the defense budget is ¾ of a trillion dollars. When war becomes that profitable you are going to see more of it.” War certainly has been extremely profitable for a few, and those few sure seem to carry a lot of weight in Washington. http://www.sonyclassics.com/whywefight/

I believe the excessive expenditure of our taxpayer dollars is due to major flaws with the incentive system. These corporations have little to gain in times of peace, especially if there is no perceived threat to our national security. The vast majority of us find peace to be more profitable than war (in the form of lower taxes), but unfortunately this is not the case for the defense contractors who have greater profits to gain in times of war and therefore, more incentives to promote war. Until we solve the incentive issue it seems likely that a small segment of the population will advocate war even if is it not in the best interest of our country…and you and I will end up paying for it.

Anarchy: The Nonexistent State

I’ve been considering Alex’s contention that Olson is wrong to simply assume banditry is to occur, or exists as some sort of necessary evil. At the time this argument was written off with the assurance that Olson understood the reality of the situation, which is that bandits will naturally crop up. However, in giving more thought to the idea I’ve realized Olson’s theories could well be applied to the question of anarchy, and explain why no stable anarchist state has ever existed or is likely too.

Let’s begin with the basics which Olson explicitly covered. The starting point which he theorizes is akin to Hobbes’s state of nature, or a sort of dog eat dog world for those unfamiliar with the philosopher. In this world there might well be productive activity going on, but there’s also a large amount of stealing because, for many, taking from another represents a way to better themselves in an easier fashion then actual production. What’s more, since there’s no entity that exists to discourage the bad behavior, there’s no real reason not to act on these impulses, assuming the thieves, or roving bandits, believe they can overpower or in some way sneak by the person currently in the position of having.

From this the supposition is that some person, or perhaps group of people, is going to realize they have more power then than their neighbors and stand to consolidate even greater power if they flex a little muscle and do a little taking to finance themselves as stationary bandits, who continue to take from their particular area of power. Now, of course, these stationary bandits have an interest in protecting those under their swath of influence from other bandits, and governments, or at the very least protection rings, begin to form.

I think this is where Alex parts ways and seems to believe one of two things, either people need not accept these bandit kings and would prefer to be without them, or the consolidation of power doesn’t necessarily have to happen at all, and some form of a permanent anarchy state would be possible.

In regards to the first, I would have to disagree. People seem to like security of some fashion, and supposing a world where at least roving bandits abound, the average person seems more likely to prefer the stationary one. I think this is actually to better ensure the process of production. If the possibility exists of being wiped out at any given moment, and could occur any number of times it would have a freezing effect on most productive activity, because activities of this nature occur only because people believe themselves likely to reap the rewards. Thus a stationary bandit, who takes a portion of your production, but leaves you at least some of it, as well as protecting you from the threat of having none due to roving bandits, while perhaps not ideal, seems infinitely preferable to the likely alternative.

In terms of the permanent anarchist state, in order for it to exist, it would require individuals to be able to protect themselves from the bandits. But in order to do this that individual, or perhaps group of individuals working together, would need to display power greater then the bandits in order to scare them off. Where does this power come from, and how is it nurtured and maintained? More then likely through a process similar to that described above, because no individual could stand for long against the combined force of an opposing group of bandits, and any commonwealth formed to fight the bandits would require some sort of tax or wage garnishing (a form of banditry) enforced by the threat of the fighting power itself in order to avoid free riders. One may ask, why the need to avoid the free rider problem? The answer is because your opponents have avoided it, and are that much more powerful because of it. Unless you can face them on somewhat equal terms you’ve consigned yourself to failure.

Thus far I’ve avoided discussion of a world without bandits entirely, roaming or stationary, as well as the idea of an benevolent power that exists solely to fight the bandits. This is because imagining it ignores the incentives of human nature. Bandits exist because it is often easier to take then to produce, as discussed earlier, and moral conundrums about it just don’t enter the equation for every member of society. A benevolent power, that does not take, but fights the enemies may well exist for some period of time, but would be unlikely to last for the same reason there are bandits. Eventually those in charge are going to want to use the power to take because the incentives for it are strong, and they have the power to do so.

Let’s begin with the basics which Olson explicitly covered. The starting point which he theorizes is akin to Hobbes’s state of nature, or a sort of dog eat dog world for those unfamiliar with the philosopher. In this world there might well be productive activity going on, but there’s also a large amount of stealing because, for many, taking from another represents a way to better themselves in an easier fashion then actual production. What’s more, since there’s no entity that exists to discourage the bad behavior, there’s no real reason not to act on these impulses, assuming the thieves, or roving bandits, believe they can overpower or in some way sneak by the person currently in the position of having.

From this the supposition is that some person, or perhaps group of people, is going to realize they have more power then than their neighbors and stand to consolidate even greater power if they flex a little muscle and do a little taking to finance themselves as stationary bandits, who continue to take from their particular area of power. Now, of course, these stationary bandits have an interest in protecting those under their swath of influence from other bandits, and governments, or at the very least protection rings, begin to form.

I think this is where Alex parts ways and seems to believe one of two things, either people need not accept these bandit kings and would prefer to be without them, or the consolidation of power doesn’t necessarily have to happen at all, and some form of a permanent anarchy state would be possible.

In regards to the first, I would have to disagree. People seem to like security of some fashion, and supposing a world where at least roving bandits abound, the average person seems more likely to prefer the stationary one. I think this is actually to better ensure the process of production. If the possibility exists of being wiped out at any given moment, and could occur any number of times it would have a freezing effect on most productive activity, because activities of this nature occur only because people believe themselves likely to reap the rewards. Thus a stationary bandit, who takes a portion of your production, but leaves you at least some of it, as well as protecting you from the threat of having none due to roving bandits, while perhaps not ideal, seems infinitely preferable to the likely alternative.

In terms of the permanent anarchist state, in order for it to exist, it would require individuals to be able to protect themselves from the bandits. But in order to do this that individual, or perhaps group of individuals working together, would need to display power greater then the bandits in order to scare them off. Where does this power come from, and how is it nurtured and maintained? More then likely through a process similar to that described above, because no individual could stand for long against the combined force of an opposing group of bandits, and any commonwealth formed to fight the bandits would require some sort of tax or wage garnishing (a form of banditry) enforced by the threat of the fighting power itself in order to avoid free riders. One may ask, why the need to avoid the free rider problem? The answer is because your opponents have avoided it, and are that much more powerful because of it. Unless you can face them on somewhat equal terms you’ve consigned yourself to failure.

Thus far I’ve avoided discussion of a world without bandits entirely, roaming or stationary, as well as the idea of an benevolent power that exists solely to fight the bandits. This is because imagining it ignores the incentives of human nature. Bandits exist because it is often easier to take then to produce, as discussed earlier, and moral conundrums about it just don’t enter the equation for every member of society. A benevolent power, that does not take, but fights the enemies may well exist for some period of time, but would be unlikely to last for the same reason there are bandits. Eventually those in charge are going to want to use the power to take because the incentives for it are strong, and they have the power to do so.

Legalize Marijuana

In class a few weeks ago we discussed the importance to distinguish self enforcing purchases from the ones enforced by the government. I think the main problem that lies with this is the illegal sector of the economy. The "black market" has to be self enforcing because they cannot rely on the government to uphold a sale, as they are all illegal. I think this fact has led to a lot of violence in this market, especially on the drug trade. People are getting injured and killed on a regular basis due to the fact they must enforce their own sales. The people who get caught selling these drugs are sent to prison where they have to become more violent just to survive. Something needs to change here. I am not suggesting legalizing all drugs, but I do think that legalizing marijuana would be a good idea as I think it would help reduce the amount of violence that goes on in the streets. The less illegal self enforcing sales there are the less violent of a society we will be.

Tuesday, April 29, 2008

A Question to Ask

Last week I was talking to a colleague/friend and I asked him what he thought our government was for. His response, though I was a little surprised, seemed par for what I would assume most Americans think what our government is for- "I think the governments responsibility is to make us more well off, to better our lives". Maybe a good experiment for this weeks discussion would be for you to ask as many people you know to tell you what they think our governments role should be in our daily lives.

A side note: he in turn asked me what I thought. When I told him that I thought the governments role was to protect our liberties and freedoms and to stay out of our lives, especially our economic ones, it was if he had never heard that before. Interesting.

A side note: he in turn asked me what I thought. When I told him that I thought the governments role was to protect our liberties and freedoms and to stay out of our lives, especially our economic ones, it was if he had never heard that before. Interesting.

Monday, April 28, 2008

I Suppose it Only Takes One

I have had this nagging question: in a nut shell, how can we trust the police? We have been discussing now for some time about how power comes about. My question has been if there was a revolution, per say, or a march on our Capital, what would keep the security (the ones with the power) from not joining the cause- what keeps a policeman loyal?

This article is about how the police are essentially corrupt, killing whenever they wish. I suppose it only takes one. Let's consider Olson and what we have learned. Assume that one cop ignores the rule of law and shoots, say a child rapist, and is concealed from the crime with help from his direct supervisor. This would definitely give the policeman incentives to continue taking the law into his own hands. Pretty soon, the entire force would be in a group that is able to do anything they want, seeing that they would have the greatest capacity for violence. I assume this is a way to see how the stationary bandit comes to power.

Maybe, the stationary bandit already has some power, like a supervisor, but does not have to show his force, but let those under him get away with using violence, while he lets it occur. If enough subordinates felt the supervisor would "ignore" there forceful evils, they would give the supervisor more power, creating a stationary bandit, if the supervisor asked them to do his "dirty work".

I wonder if this is consistent with what we have learned. I suggest that the stationary bandit(SB) does not use force himself, but by allowing it to happen, he becomes more powerful. I wonder, though, what would happen if the SB never showed force (i.e. killing someone) if one of the subordinates would "challenge" him with force. Or, maybe more simply, can an OZ really exist- does it take only one?

This article is about how the police are essentially corrupt, killing whenever they wish. I suppose it only takes one. Let's consider Olson and what we have learned. Assume that one cop ignores the rule of law and shoots, say a child rapist, and is concealed from the crime with help from his direct supervisor. This would definitely give the policeman incentives to continue taking the law into his own hands. Pretty soon, the entire force would be in a group that is able to do anything they want, seeing that they would have the greatest capacity for violence. I assume this is a way to see how the stationary bandit comes to power.

Maybe, the stationary bandit already has some power, like a supervisor, but does not have to show his force, but let those under him get away with using violence, while he lets it occur. If enough subordinates felt the supervisor would "ignore" there forceful evils, they would give the supervisor more power, creating a stationary bandit, if the supervisor asked them to do his "dirty work".

I wonder if this is consistent with what we have learned. I suggest that the stationary bandit(SB) does not use force himself, but by allowing it to happen, he becomes more powerful. I wonder, though, what would happen if the SB never showed force (i.e. killing someone) if one of the subordinates would "challenge" him with force. Or, maybe more simply, can an OZ really exist- does it take only one?

What Really Happens with Forecloseure

I just skimmed an article that talked about why I should be concerned if my neighbors house forecloses. Though I just skimmed the article, the just was that when a house becomes foreclosed, there is a spike in crime and drugs in the neighborhood. I suppose this may be true for most, but I think it is a fallacy to generalize for all. Here is how I think it should be.

Now, most of you know me by now and know I am the furthest from a socialist. However, I think this "housing mess" could be handled in a different way. The press sees this crisis as a cause for government intervention- how wrong. I suppose that we could think of the other homeowners in the area as a group. They all have a stake in the conditions of the houses around them- one house is trashy, property values decline. So in order for their property values to stay up, I would think that homeowners (in a non-covenant setting) in a neighborhood would look out for each other. When they would see a homeowner in trouble, they would help him out, not a government bailout! And if the house is foreclosed upon, helping keep up basic upkeep and keeping an eye out on the house would help to prevent drugs and crime from setting into the house.

I have a friend who is in such a situation and he keeps an eye on the foreclosed house. This, I think, shows how neighbors, and not government, can work together to bring prosperity to everyone in the neighborhood.

Now, most of you know me by now and know I am the furthest from a socialist. However, I think this "housing mess" could be handled in a different way. The press sees this crisis as a cause for government intervention- how wrong. I suppose that we could think of the other homeowners in the area as a group. They all have a stake in the conditions of the houses around them- one house is trashy, property values decline. So in order for their property values to stay up, I would think that homeowners (in a non-covenant setting) in a neighborhood would look out for each other. When they would see a homeowner in trouble, they would help him out, not a government bailout! And if the house is foreclosed upon, helping keep up basic upkeep and keeping an eye out on the house would help to prevent drugs and crime from setting into the house.

I have a friend who is in such a situation and he keeps an eye on the foreclosed house. This, I think, shows how neighbors, and not government, can work together to bring prosperity to everyone in the neighborhood.

Sunday, April 27, 2008

The Russian Oil Taxes…… Ouch!

"It's never easy to find $1 trillion in investment capital, but the Russian government has made it hard for its oil industry to attract even a small part of that capital. The Kremlin has structured taxes so that most of the extraordinary rise in oil prices flows into government coffers, not oil-company profits.

When oil rises above $27 a barrel, the Russian government takes 80% of any additional revenue in taxes. That means at $67 a barrel, an oil company gets just $8 more a barrel in revenue than at $27. If the price climbs to $107 a barrel, the oil company's revenue increases by just $16 a barrel from what it was at $27 a barrel.

That may delight U.S. consumers who believe oil companies are making obscene windfall profits from soaring oil prices, but it hasn't made companies eager to sink their money into developing new oil in Russia.

The production decline in Russia would be serious enough if it were an isolated problem. But it's not. The same conjunction of geology and geopolitics is crimping production in Nigeria and Mexico."

the link to full article

http://articles.moneycentral.msn.com/Investing/JubaksJournal/WhyOilCouldHit180DollarsABarrel.aspx

This was an excerpt from a recent article link on the MSN website. Jubak was talking about how oil will go to $180 a barrel and most likely stay there. The most interesting part of the article I thought was this part. It’s hard to imagine that the Russian government has the tax system setup this way to really suck the life out of the oil industry not to mention the potential investors. Looking at it from a Power and Prosperity point of view we can clearly see the predation by the government. How will the oil industry grow and prosper with a government that takes 80% of the revenue? Most of the “greenies” here in America talk about getting off the dependence of oil. Over there the people should be talking about getting the government off the dependence of oil for revenue!

Add the money they bring in from the oil industry predation to the corruption and you get the Russian government. Wow, it’s so easy to see what Olson is talking about in Power and Prosperity. This could be one place the Russian government could fix to increase oil production and revenue for the firms and also increase investment. If the Russian government takes this amount in taxes from the oil industry, imagine what it takes in other industries. We do hear of the Russian come back, but imagine what it could do without this predation by the government.

When oil rises above $27 a barrel, the Russian government takes 80% of any additional revenue in taxes. That means at $67 a barrel, an oil company gets just $8 more a barrel in revenue than at $27. If the price climbs to $107 a barrel, the oil company's revenue increases by just $16 a barrel from what it was at $27 a barrel.

That may delight U.S. consumers who believe oil companies are making obscene windfall profits from soaring oil prices, but it hasn't made companies eager to sink their money into developing new oil in Russia.

The production decline in Russia would be serious enough if it were an isolated problem. But it's not. The same conjunction of geology and geopolitics is crimping production in Nigeria and Mexico."

the link to full article

http://articles.moneycentral.msn.com/Investing/JubaksJournal/WhyOilCouldHit180DollarsABarrel.aspx

This was an excerpt from a recent article link on the MSN website. Jubak was talking about how oil will go to $180 a barrel and most likely stay there. The most interesting part of the article I thought was this part. It’s hard to imagine that the Russian government has the tax system setup this way to really suck the life out of the oil industry not to mention the potential investors. Looking at it from a Power and Prosperity point of view we can clearly see the predation by the government. How will the oil industry grow and prosper with a government that takes 80% of the revenue? Most of the “greenies” here in America talk about getting off the dependence of oil. Over there the people should be talking about getting the government off the dependence of oil for revenue!

Add the money they bring in from the oil industry predation to the corruption and you get the Russian government. Wow, it’s so easy to see what Olson is talking about in Power and Prosperity. This could be one place the Russian government could fix to increase oil production and revenue for the firms and also increase investment. If the Russian government takes this amount in taxes from the oil industry, imagine what it takes in other industries. We do hear of the Russian come back, but imagine what it could do without this predation by the government.

Those Free Riding ______!

During time in between classes last week we had a discussion about how America is always fighting wars somewhat alone. It seems as though there is not really all that much involvement in conflicts by other countries that are a part of the “functioning core” as Barnett calls them. We see that American forces are stepping in to conflicts but we don’t here too much of France, Germany, Spain or Italy hoping on to the bandwagon to help out. Professor Eubanks had the idea that the number of soldiers in these countries probably have declined over the years because of the logic of collective action.

I took a look at the number of soldiers in the German army over the 90’s and early part of the 21’st century and found that there was a decline in the number of soldiers. At the beginning of the 90’s there were over 255,000 soldiers and by 2000 there were only 230,000.

Applying the logic of collective action to the number of soldiers seems to be proven true that the numbers would go down, but why? Well the answer is: they are free riding. Think of it this way, each country is part of a group of countries. As the number of countries in this group grows it becomes a large group. Well we all know that large groups do not function unless they offer selective incentives or have an element of coercion to force the countries to do things. Well if there are no selective incentives which there are none and each country cannot force another country to help out, then you will get free riders. I think that is what is happening now, America is stuck doing all the work well the free riding jerks are just sitting back and watching. There are a number of countries that could help out with rebuilding Iraq but no, you don’t hear of them really putting the large number of soldiers out there. All they do is complain about what we do. This is why their numbers have fallen, because they think America can do the work. Why have so many soldiers when it’s not going to match the numbers or power of the American forces? The logic of collective action rings true again. Large groups don’t work, and free riders always cruse along for the ride.

I took a look at the number of soldiers in the German army over the 90’s and early part of the 21’st century and found that there was a decline in the number of soldiers. At the beginning of the 90’s there were over 255,000 soldiers and by 2000 there were only 230,000.

Applying the logic of collective action to the number of soldiers seems to be proven true that the numbers would go down, but why? Well the answer is: they are free riding. Think of it this way, each country is part of a group of countries. As the number of countries in this group grows it becomes a large group. Well we all know that large groups do not function unless they offer selective incentives or have an element of coercion to force the countries to do things. Well if there are no selective incentives which there are none and each country cannot force another country to help out, then you will get free riders. I think that is what is happening now, America is stuck doing all the work well the free riding jerks are just sitting back and watching. There are a number of countries that could help out with rebuilding Iraq but no, you don’t hear of them really putting the large number of soldiers out there. All they do is complain about what we do. This is why their numbers have fallen, because they think America can do the work. Why have so many soldiers when it’s not going to match the numbers or power of the American forces? The logic of collective action rings true again. Large groups don’t work, and free riders always cruse along for the ride.

More Likely, Not Less

Recently MAX BOOT CONSIDERS comments on Admiral Fallon:

"What Fallon (and Barnett) don't seem to understand is that Fallon's very public assurances that America has no plans to use force against Iran embolden the mullahs to continue developing nuclear weapons and supporting terrorist groups that are killing American soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan. It is highly improbable that, as the profile implies, the president had any secret plans to bomb Iran that Fallon put a stop to. But there is no doubt that the president wants to maintain pressure on Iran, and that's what Fallon has been undermining.Considering Olson's Power & Prosperity what is your view of this assertion that Admiral Fallon made armed confrontation more likely, not less likely?

By irresponsibly taking the option of force off the table, Fallon makes it more likely, not less, that there will ultimately be an armed confrontation with Iran."

Thursday, April 17, 2008

Why are wages declining?

In thinking about Economic Policy Analysis, I found an interesting link.

http://www.newschool.edu/cepa/

Considering CEPA stands for Center for Economic Policy Analysis, I think I've struck gold!

In reading through some of the abstracts, I found an article:

Increasing Earnings Inequality and Unemployment in Developed Countries: Markets, Institutions and the ‘Unified Theory’

by David R. Howell (CEPA)

“Fundamentally, the demand for less-skilled workers appears to be declining faster than the number of less-skilled workers, and their wages are therefore drawn downward.”

OECD, OECD Jobs Study, Evidence and Explanations, Part I: (Paris:OECD, 1994), 30.

So what does this mean? Well, it's a question that will lead to my exploration and thus final paper, writing an actual policy analysis, but what I think it implies at this point is simply this. One side of the argument might argue that unskilled labor ought to be protected through policy and justified by this policy analysis. The other side might argue that through specialization, markets may emerge, causing shifts of those who are unskilled labor to actually develop a skill that would allow them to attain better prosperity.

Though aggregation is a dangerous thing to do, the logic of collective action suggests that people will voluntarily align with others to form a group, thus making aggregation justified. In this vein, if those in a position to emphasize certain points of agenda decide to move towards unskilled labor industries, then they may actually be causing harm; whereas if they were to offer incentives to the 'group' to specialize and work as skilled labor, they may actually prevent harm from occurring.

We've spoken of roving and stationary bandits in terms of government and power and prosperity, but what about in terms of international power and prosperity? Considering that we won't move to one single over-seeing power in the world, we have economics to help us understand that power and prosperity is a dynamic phenomenon and that through paying attention to trends, we might understand what policy to implement. If "demand for unskilled labor" is going down, then wouldn't it make sense to get involved in some sort of specialized skill so as to avoid the repurcussions of declining demand? At individual levels, this makes perfect sense and it is assumed (by many) that this is how economics are applied on the small scale. But at larger levels, where collective action occurs, where government policy is influenced by special interest, then how could the argument to protect unskilled labor prevail in lue of this analysis?

Perhaps this has something to do with predatory governments and limited liberties of the governed.

http://www.newschool.edu/cepa/

Considering CEPA stands for Center for Economic Policy Analysis, I think I've struck gold!

In reading through some of the abstracts, I found an article:

Increasing Earnings Inequality and Unemployment in Developed Countries: Markets, Institutions and the ‘Unified Theory’

by David R. Howell (CEPA)

“Fundamentally, the demand for less-skilled workers appears to be declining faster than the number of less-skilled workers, and their wages are therefore drawn downward.”

OECD, OECD Jobs Study, Evidence and Explanations, Part I: (Paris:OECD, 1994), 30.

So what does this mean? Well, it's a question that will lead to my exploration and thus final paper, writing an actual policy analysis, but what I think it implies at this point is simply this. One side of the argument might argue that unskilled labor ought to be protected through policy and justified by this policy analysis. The other side might argue that through specialization, markets may emerge, causing shifts of those who are unskilled labor to actually develop a skill that would allow them to attain better prosperity.

Though aggregation is a dangerous thing to do, the logic of collective action suggests that people will voluntarily align with others to form a group, thus making aggregation justified. In this vein, if those in a position to emphasize certain points of agenda decide to move towards unskilled labor industries, then they may actually be causing harm; whereas if they were to offer incentives to the 'group' to specialize and work as skilled labor, they may actually prevent harm from occurring.

We've spoken of roving and stationary bandits in terms of government and power and prosperity, but what about in terms of international power and prosperity? Considering that we won't move to one single over-seeing power in the world, we have economics to help us understand that power and prosperity is a dynamic phenomenon and that through paying attention to trends, we might understand what policy to implement. If "demand for unskilled labor" is going down, then wouldn't it make sense to get involved in some sort of specialized skill so as to avoid the repurcussions of declining demand? At individual levels, this makes perfect sense and it is assumed (by many) that this is how economics are applied on the small scale. But at larger levels, where collective action occurs, where government policy is influenced by special interest, then how could the argument to protect unskilled labor prevail in lue of this analysis?

Perhaps this has something to do with predatory governments and limited liberties of the governed.

Corruption

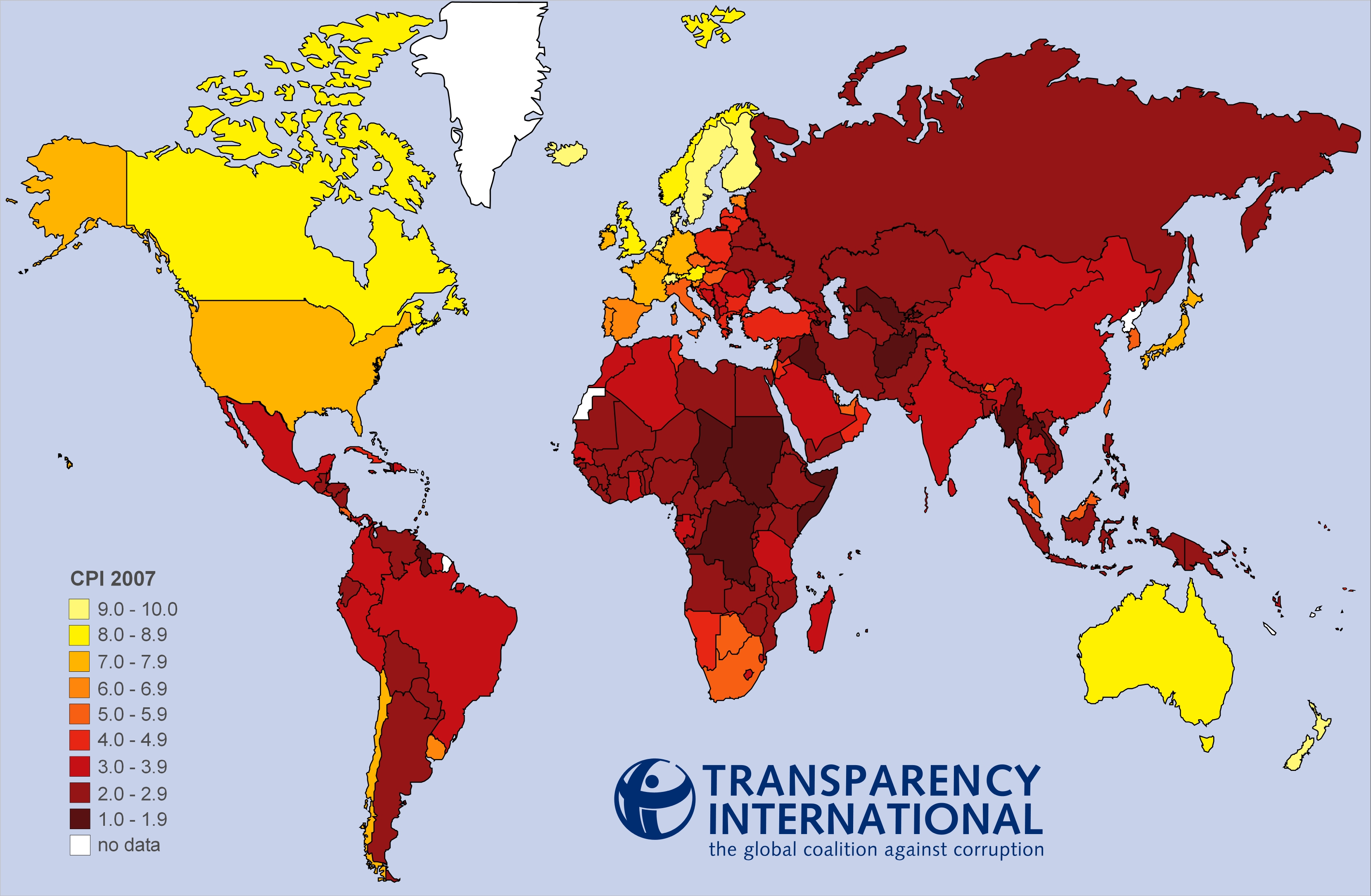

Since corruption was part of our readings this week I thought you might be interested in the "corruption perceptions index." In checking out the map above you can guess that the darkest shade of read represents lots of corruption.

TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL is the organization that puts together the corruption index.

Monday, March 31, 2008

Chipping away at my liberal ideals

The duality between my conservative tendencies and my liberal instincts keeps becoming more and more distinct. I am absolutely no longer amused about the situations in the world's poorest and most violent countries. I tire of, after hours of research and surfing Wikipedia, confirming to be mostly false the politically correct notions of why the African third-world is in poverty and seeming perpetual misery and what can be done to solve those things. I tire of hearing all these amusing anecdotes from left-wing citizens of Fantasyworld about how they did such things as join the Peace Corps or how they donated money to help save Darfur or how they think it's disgusting that the US only donates something like .002% of its GDP to global monetary aid to the third world (compared to Western European countries, which donate substantially more as a function of their GDP).

I tire of all this for the same reason I have begun to get sick of many liberalist ideas: they work very well in the abstract, but they don't translate well into reality when you consider the negative aspects of human nature. And many of these negative things, I believe, probably have far more to do with explanations vested in nature than in nurture. This is important because if this is true, then on a macro scale it means that many of the problems we have today will never go away, and many of the inequalities we see on a micro and macro scale will probably never go away, even though they might lessen.

The idea that there is inequality that exists and will never be neutralized is a hard idea to accept to someone who cares or has a fundamentally optimistic view of the world and of people (ie, a liberal). However, this is a necessary concept to accept in order to be able to make tangible policy decisions and be able to render effective solutions.

At the same time, accepting such a notion is, correctly, probably evil. This duality I have described is one that I have understood for some time. However, in the past I have advocated as part of my philosophy on life that shooting for the idea, even if the ideal is unrealistic or unlikely, is the correct and civilized thing to do, because in the abstract it is beautiful, and that had value to me. I would say that the IMF, donating money to causes such as Darfur and Feed the Children, etc. are good things, even if the chances of them actually doing something positive are low (but not zero).

Now, however, I don't believe I feel this way anymore. I have come to conclude that the ideal is more fantastical than I had hoped. Also, I believe the differences amongst peoples and cultures are deeper than one would like to think. When you combine this with my belief that there are at least some things about life and of humanity that are absolute and universal, and that therefore value judgements can be made about one culture versus another, the result is a painful move towards pessimism. I do think that our Western culture and way of life is superior. Is it our right or responsibility to force what we know to be better onto other cultures, or at least try to? I don't believe so, but partly because I believe it is not realistic to expect it to work. We see this in Iraq. It is a people's obligation to steward its own destiny.

What do we do with a Haiti, or a Sierra Leone? Do you ignore it and watch as it wallows in misery? Do you throw money and aid and resources at it, even though it has been shown that those things will make little to no difference in allaying the misery? Do you hold as official policy some ethereal notion that "expanding and liberalizing trade and privatizing the economy" will solve any problem?

There is no right answer, because in these situations there is no solution. Food for thought: one of the only large differences between the early progression of South Africa and the progression of the US as countries is that the native population of the US was practically exterminated by Smallpox before Europeans really began settling and migrating west, rendering the whole continent easily conquerable. This never happened in South Africa, and the Europeans were not able to penetrate the continent as a result; the natives were not killed en masse. If it were not for Smallpox (and subsequent quasi-ethnic cleansing that the US engaged in until the late 1800's), the US might very well resemble closely South Africa today, a country clinging to life of the size of the current Eastern Seaboard, perhaps, with a minority white population and little global relevance or power.

I am not necessarily advocating that the Smallpox or the killing were good things at all. Some of the things that the Americans did were horrid. However, when one considers what the US is today (I consider it to be a wonderful thing), one would be ignorant to ignore the painfully conflicting ideologies that result.

Capitalism embraces the negative aspects of human nature. That's why it works.

Safety in Groups

Reading through some of the previous posts I’ve noticed more than one focus on the idea defense and protection as a public good, the most recent being “A Public Good Via Self-Defense” by Michelle Rennolet. And while these articles do a good job reviewing Olson’s theory of collective action as it may apply to such a good and the applications thereof, I’d like to continue along the same lines, but now spend a little time covering some of the actual groups that have sprung up with an eye towards providing public defense, and invite all the previous posters to join in and highlight wherever I may get it wrong.

Now the most obvious groups that exist to provide defense are the United States Armed Forces. However, the incentive that brings members of this group together, outside of providing national defense, something that benefits soldiers as well as nonsoldiers, is obvious. It’s a job that not just provides a paycheck but many other benefits, such as transferable training and college scholarships. So while membership requires no coercion (except in times of a draft) providing for the costs of membership is a little different. Paying soldiers is an expensive endeavor, and one that would undoubtedly encounter free rider problems if left purely to good natured contributions from those attempting to pay for the public good provided for them. Thus the ultimate form of coercion is required in the form of compulsory government taxes.

There are, however, true volunteer groups that attempt, or at least claim, to provide for public safety. Let’s begin with militias. The question to ask here should be why members show up at all. Unlike the armed forces and local police there’s no pay and honestly, there’s little to no good being provided as there hasn’t been much call for militias to bolster national defense since the early 1800s. Thus if the good provided by the group is negligible at best, we could assume the benefit to each individual member to be less then minute, while the drain on time and energy continues to be constant. Why then continue to attend meetings and target practices? I think the answer is social incentives. Most militias, outside of the Texas Minutemen who claim to guarding the border, have devolved into something more akin to a club then a serious gathering. The true interests are in laughs and companionship not national defense.

Among the other volunteer groups you hear about attempting to provide a public good, perhaps the most often mentioned is the neighborhood watch. This is a bit of an interesting case because it varies from formation to formation. Often they’re formed in neighborhoods with little crime to begin with and can thus be chalked up to social incentives again, with the weekly meetings taking the place of ye olde neighborhood picnics and such forth. However, in other cases there is a specific need involved because of high crime rates, or a sudden local crime spree, and here I think the small group dynamic comes into play. In essence the benefit provided to each individual member is at least equal if not greater then the effort put out. A meeting and patrol every now and then isn’t high effort and neither is agreeing to call the cops or check in with neighbors if you witness something suspicious. But in high crime neighborhoods the benefit of getting your neighbors to do the same can be of untold value. Of course there’s still likely to be a free rider problem to some extent, but in a small group like this social pressure rather then incentives can prove to be the deciding factor in getting everyone on board.

-Jaeson Madison

Now the most obvious groups that exist to provide defense are the United States Armed Forces. However, the incentive that brings members of this group together, outside of providing national defense, something that benefits soldiers as well as nonsoldiers, is obvious. It’s a job that not just provides a paycheck but many other benefits, such as transferable training and college scholarships. So while membership requires no coercion (except in times of a draft) providing for the costs of membership is a little different. Paying soldiers is an expensive endeavor, and one that would undoubtedly encounter free rider problems if left purely to good natured contributions from those attempting to pay for the public good provided for them. Thus the ultimate form of coercion is required in the form of compulsory government taxes.

There are, however, true volunteer groups that attempt, or at least claim, to provide for public safety. Let’s begin with militias. The question to ask here should be why members show up at all. Unlike the armed forces and local police there’s no pay and honestly, there’s little to no good being provided as there hasn’t been much call for militias to bolster national defense since the early 1800s. Thus if the good provided by the group is negligible at best, we could assume the benefit to each individual member to be less then minute, while the drain on time and energy continues to be constant. Why then continue to attend meetings and target practices? I think the answer is social incentives. Most militias, outside of the Texas Minutemen who claim to guarding the border, have devolved into something more akin to a club then a serious gathering. The true interests are in laughs and companionship not national defense.

Among the other volunteer groups you hear about attempting to provide a public good, perhaps the most often mentioned is the neighborhood watch. This is a bit of an interesting case because it varies from formation to formation. Often they’re formed in neighborhoods with little crime to begin with and can thus be chalked up to social incentives again, with the weekly meetings taking the place of ye olde neighborhood picnics and such forth. However, in other cases there is a specific need involved because of high crime rates, or a sudden local crime spree, and here I think the small group dynamic comes into play. In essence the benefit provided to each individual member is at least equal if not greater then the effort put out. A meeting and patrol every now and then isn’t high effort and neither is agreeing to call the cops or check in with neighbors if you witness something suspicious. But in high crime neighborhoods the benefit of getting your neighbors to do the same can be of untold value. Of course there’s still likely to be a free rider problem to some extent, but in a small group like this social pressure rather then incentives can prove to be the deciding factor in getting everyone on board.

-Jaeson Madison

Athletes vs. Farmers

What do Chinese farmers and the Olympics athletes have in common? Water. During the Olympics that will be held in Beijing this summer, the city’s water demand is expected to spike up by 30 percent above average. The northern province of Hebei provides the majority of Beijing’s water. Unfortunately, this province is now suffering severe drought due to a lack of winter rain and snow. The four dams that supply water to the regional farmers and the city of Beijing are reported to be 60% lower than average. On top of the current water shortage, China is in the process of building 309km of channels to draw water from the four Hebei dams to the city of Beijing. These channels are intended to bring an extra 300 million cubic meters of water to be used as a “back-up” supply during the time of the Olympics. What will be the consequences of this move? The drought has already affected 1.89 million head of livestock and left 2.43 million people without sufficient drinking water. According to the World Fact book, 43 percent of the Chinese population is employed in agricultural. What will happen to the Hebei farmers if they lose another 300 million cubic meters of water to the city? In China’s efforts to make a good impression on the international community and boost their economy by hosting the Olympics they are creating a situation that will potentially have many unintended consequences. Is it worth jeopardizing the health and livelihood of so many people for the sake of having “green” games and making Beijing the sparkling host city of the 2008 Olympics?

http://sport.guarding.co.uk/breakingnews.html

http://sport.guarding.co.uk/breakingnews.html

California Prison Guards

Unless drastic measures are taken, California will soon be spending more tax dollars on its state prison system than its public universities. Schwarzenegger’s 2007-2008 state budget even shells out more than our federal prison system - $3.3 billion more – even though federal prisons house almost 30,000 more prisoners.

The wealth of knowledge I gained while reading Mancur Olson lead me to believe that there was something more to this excessive expenditure of taxpayer dollars, so I decided to do a little research. Of course, I didn’t have to look far, for the second article that popped up on my google search was labeled “The California Prison Guards’ Union: A Potent Political Interest Group”. http://thirdworldtraveler.com/Prison_System/CalifPrisonGuards.html

Author Dan Pens eloquently states that there is “a well fed Political Interest Group feasting at the California public trough, and most taxpayers are unaware of the huge growth in this creature’s appetite and political clout.” The California Correctional Peace Officer’s Association’s (CCPOA) sudden rise to power began in the year 1980 with the installation of Don Novey as the CCPOA president. The ambitious Novey exhibited true genius in the arena of political lobbying, increasing prison guards’ salaries from $14,400 a year in 1980 to $44,000 a year in 1996 – an amount that totaled well over $50,000 a year with benefits. That amount was $10,000 more than the average teacher’s salary in 1996, quite a large sum when one considers that the position of prison guard requires only a high school diploma while a teaching position demands at least a four year college degree.

Novey found it all too easy to exert tremendous influence over California’s politicians, for as one would expect “there are no vested interests against spending more on prisons.” Everyone wants “to keep thugs off the streets and in jail where they belong” and no politician wants to be known as the man who was soft on crime, so the state prison budget steadily grew as the CCPOA’s influence increased.

Obviously the extra funds committed to the prisons must come from somewhere, so it should come as no surprise that the California prison budget has grown at the expense of other public programs, most notably higher education. In 1983-1984, California spent only 3.9 percent of its budget on its correctional systems and 10 percent on its public universities. The meteoric rise to power of the CCPOA will produce correctional system spending levels that are set to pass higher education expenditures in less than 5 years. Don Novey must be very proud.

The expansion of prison funding has also resulted in a tax increase. This tax increase has prompted a massive exodus of corporations and as these corporations flee they take with them thousands of jobs, leaving fewer taxpayers to shoulder the added tax burden.

Dan Pens concludes his article by speculating that “only after the state drives itself into an abyss that a radical revolutionary shift can take place.” Sadly, I believe he may be right.

The wealth of knowledge I gained while reading Mancur Olson lead me to believe that there was something more to this excessive expenditure of taxpayer dollars, so I decided to do a little research. Of course, I didn’t have to look far, for the second article that popped up on my google search was labeled “The California Prison Guards’ Union: A Potent Political Interest Group”. http://thirdworldtraveler.com/Prison_System/CalifPrisonGuards.html

Author Dan Pens eloquently states that there is “a well fed Political Interest Group feasting at the California public trough, and most taxpayers are unaware of the huge growth in this creature’s appetite and political clout.” The California Correctional Peace Officer’s Association’s (CCPOA) sudden rise to power began in the year 1980 with the installation of Don Novey as the CCPOA president. The ambitious Novey exhibited true genius in the arena of political lobbying, increasing prison guards’ salaries from $14,400 a year in 1980 to $44,000 a year in 1996 – an amount that totaled well over $50,000 a year with benefits. That amount was $10,000 more than the average teacher’s salary in 1996, quite a large sum when one considers that the position of prison guard requires only a high school diploma while a teaching position demands at least a four year college degree.

Novey found it all too easy to exert tremendous influence over California’s politicians, for as one would expect “there are no vested interests against spending more on prisons.” Everyone wants “to keep thugs off the streets and in jail where they belong” and no politician wants to be known as the man who was soft on crime, so the state prison budget steadily grew as the CCPOA’s influence increased.

Obviously the extra funds committed to the prisons must come from somewhere, so it should come as no surprise that the California prison budget has grown at the expense of other public programs, most notably higher education. In 1983-1984, California spent only 3.9 percent of its budget on its correctional systems and 10 percent on its public universities. The meteoric rise to power of the CCPOA will produce correctional system spending levels that are set to pass higher education expenditures in less than 5 years. Don Novey must be very proud.

The expansion of prison funding has also resulted in a tax increase. This tax increase has prompted a massive exodus of corporations and as these corporations flee they take with them thousands of jobs, leaving fewer taxpayers to shoulder the added tax burden.

Dan Pens concludes his article by speculating that “only after the state drives itself into an abyss that a radical revolutionary shift can take place.” Sadly, I believe he may be right.

Sunday, March 30, 2008

South Africa

I recently went to a conference about the economics of South Africa. They had swithched their government process about a decade ago and their economy has been headed up ever since. They dropped the procedures that they had been using, cleaned house, and started fresh. In The Rise and Decline of Nations Mancur Olson talks about how an upheaval and change is a way that many economies get a boost. Finding out some of the information about how much more successful the new economy has been was just more evidence to Olson's stance. Everything that he stated in that book, particularly in Chapter 4 was validated in this conference. Although they still have a long way to go the economy there is looking up, and it is because they had a complete restart on the way they do things. I have tended to agree with Olson anyway, but this was just more validation for what he states in his book.

Friday, March 21, 2008

Zimbabwe

As we turn to Olson's Power and Prosperity, you might be interested in considering the views of MORGAN TSVANGIRAI, a presidential candidate in Zimbabwe's upcoming elections:

As the March 29 election in Zimbabwe approaches, the cards are clearly stacked in favor of President Robert Mugabe and his ZANU-PF party. Draconian legislation has curtailed freedom of expression and association. Daily, the representatives of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), the political party that I lead, are harassed, tortured, imprisoned without trial and even killed.If you lived in Zimbabwe, would you vote for this candidate? His views certainly seem consistent with Olson's Power and Prosperity. Come to think of it, I would like to hear candidates for our presidency who seemed to understand as much about power and prosperity as Mr. Tsvangirai does.

Economic mismanagement by Mr. Mugabe's government is an even more serious problem. Zimbabwe's inflation and unemployment rates are 150,000% and 80% respectively. Infrastructure is crumbling, and education and health-care systems have collapsed. Life expectancy is now among the lowest in the world, having declined, since 1994, to 34 years from 57 years for women, and to 37 years from 54 for men. Some four million of my fellow citizens have fled the country, taking with them both human and financial capital.

Out of the many reasons for Zimbabwe's decline, three stand out. First is the ruling regime's contempt for the rule of law. The government has repeatedly stole elections, and intimidated, beaten and murdered its opponents. It has confiscated private property without compensation and ignored court rulings declaring such takings illegal. Such behavior only scares away investors, domestic and international. Current circumstances make it impossible to have a growing economy that will create jobs for millions of unemployed Zimbabweans.

[ . . . ]

The second reason for Zimbabwe's decline is the government's destruction of economic freedom, in order to satisfy an elaborate patronage system.

Today, Zimbabwe ranks last out of the 141 countries surveyed by the Fraser Institute's Economic Freedom in the World report. According to 2007 World Bank estimates, it takes 96 days to start a business in Zimbabwe. It takes only two days in Australia. Waiting for necessary licenses takes 952 days in Zimbabwe, but only 34 days in South Korea. Registering property in Zimbabwe costs an astonishing 25% of the property's value. In the United States, it costs only 0.5%.

[ . . . ]

The third factor responsible for the country's decline is the size and rapaciousness of the government. Today, that size is determined by the requirements of patronage. But a government that provides hardly any public services cannot justify the need for 45 ministers and deputy ministers, all of whom enjoy perks ranging from expensive SUVs to farms that were confiscated from others.

The Central Bank too has departed from its traditional role of stabilizing prices. Instead, it dishes out money to dysfunctional, government-owned corporations that are controlled by the ZANU-PF and are accountable to no one. The result is runaway growth in the money supply, and the highest inflation rate in the world. Zimbabwe's potential for economic growth cannot be realized without macroeconomic stability. Hyperinflation must be tamed, in part by taming the government's appetite for spending.

Thursday, March 20, 2008

Sub-prime Crisis? Yeah, right.

There is perhaps a moderate economic crisis looming in the not-too-distant future, with the sub-prime crisis in swing, and there is some reason to worry that another economic boom is going to be in the distant future as opposed to the near one.

However, I believe that these concerns are largely exaggerated. The hegemony of the US economically is not something that can be disturbed easily, something that was certainly not true prior to 1950. Even the worst-case scenario economic ramifications of the sub-prime crisis do not really rival some other "crises" that the US has experienced in the last 50 years.

For one, the petroleum shortages of the late 70's and early 80's were a far greater macro threat to our economy. Back then the US's economy was far more dependent and reliant on petroleum than it is now (it's true). Inflation was off the charts (highest levels in modern history, at least in 100 years in the US), and interest rates were fluctuating wildly. Nothing short of the death of American auto was at hand, and Paul Volker, bless his soul, was doing his best to try and stem the tide. Any economics professor will easily tell you (and will have the graphs to prove it) that the early 80's was easily the most volatile time economically since the Depression. An assortment of figures and data points from the era would show up on econ graphs as statistical anomalies inconsistent with trends of before and after.

And you know what? America didn't hit the fan. There was recovery (which had some, but not everything to do with, Reaganomics). It wasn't the Great Depression II. And life moved on. Gas prices now are, in real terms, still not even as high as they were in 1982 (I believe it's getting close). America didn't collapse into a pile of anarchy and chaos.

A more comparable analogy would be the S&L scandal, also in the 1980's. Thanks to President [deleted by Professor] Reagan, the American public ended up losing something like $300 billion (I'm too lazy to look up the real amount, but it's big) in the government's bailout of all the private S&L's that went under. The government was partly to blame, amid scandal and probably corruption and collusion. You want to talk about bank failure though? This was the time to talk about it. The ramifications of the S&L scandal also far surpass anything we have today.

And yet we're still here.

Inflation happens. Stagflation happens. And neither of these things are happening now in amounts that even remotely rival the 1980's.

And as far as the Depression goes... yes the stock market is volatile. Yes it is subject to crashes. However, the Great Depression had many causes, and the stock market crash had little to do with it. It was certainly the cause, but the Fed back then had no idea how to handle things. Deflation was going on. The Fed should have pumped money into the supply. It didn't. If it would have, there would likely have been recovery (if it did that and a few other things) in relatively short order.

Now, there is the whole China-could-pull-the-plug-on-us-and-plunge-our-nation-into-anarchy-and-war-and-chaos-if-they-wanted-to thing, but that's another story. And it's extremely unlikely anyway.

Peak Oil? Hmmm. I'm not sold. The energy companies will get off their keisters and develop alternative energy when it becomes economically feasible. I'm confident of this.

Maybe I'm too optimistic.

However, I believe that these concerns are largely exaggerated. The hegemony of the US economically is not something that can be disturbed easily, something that was certainly not true prior to 1950. Even the worst-case scenario economic ramifications of the sub-prime crisis do not really rival some other "crises" that the US has experienced in the last 50 years.

For one, the petroleum shortages of the late 70's and early 80's were a far greater macro threat to our economy. Back then the US's economy was far more dependent and reliant on petroleum than it is now (it's true). Inflation was off the charts (highest levels in modern history, at least in 100 years in the US), and interest rates were fluctuating wildly. Nothing short of the death of American auto was at hand, and Paul Volker, bless his soul, was doing his best to try and stem the tide. Any economics professor will easily tell you (and will have the graphs to prove it) that the early 80's was easily the most volatile time economically since the Depression. An assortment of figures and data points from the era would show up on econ graphs as statistical anomalies inconsistent with trends of before and after.

And you know what? America didn't hit the fan. There was recovery (which had some, but not everything to do with, Reaganomics). It wasn't the Great Depression II. And life moved on. Gas prices now are, in real terms, still not even as high as they were in 1982 (I believe it's getting close). America didn't collapse into a pile of anarchy and chaos.

A more comparable analogy would be the S&L scandal, also in the 1980's. Thanks to President [deleted by Professor] Reagan, the American public ended up losing something like $300 billion (I'm too lazy to look up the real amount, but it's big) in the government's bailout of all the private S&L's that went under. The government was partly to blame, amid scandal and probably corruption and collusion. You want to talk about bank failure though? This was the time to talk about it. The ramifications of the S&L scandal also far surpass anything we have today.

And yet we're still here.

Inflation happens. Stagflation happens. And neither of these things are happening now in amounts that even remotely rival the 1980's.

And as far as the Depression goes... yes the stock market is volatile. Yes it is subject to crashes. However, the Great Depression had many causes, and the stock market crash had little to do with it. It was certainly the cause, but the Fed back then had no idea how to handle things. Deflation was going on. The Fed should have pumped money into the supply. It didn't. If it would have, there would likely have been recovery (if it did that and a few other things) in relatively short order.

Now, there is the whole China-could-pull-the-plug-on-us-and-plunge-our-nation-into-anarchy-and-war-and-chaos-if-they-wanted-to thing, but that's another story. And it's extremely unlikely anyway.

Peak Oil? Hmmm. I'm not sold. The energy companies will get off their keisters and develop alternative energy when it becomes economically feasible. I'm confident of this.

Maybe I'm too optimistic.

Thursday, March 06, 2008

A Loophole? Really?

What luck! Talking today about political entrepreneurs and low and behold an article specifically about them.

The article talks about how a recent smoking ban in Minnesota has a loophole that "contains an exception for performers in theatrical productions." So, bars are allowing "theatre performers" to smoke all night. The loophole, which we will speculate in a moment, was found by a political entrepreneur (actually a lawyer, but then who better?).

As we have discussed in class, a law passed by a citizen vote (democracy), like the one we have in the state of Colorado, is different from the law passed by the legislature in Minnesota. We should then look for who wanted the law passed in Minnesota. My guess would be those restaurants that have gone to no smoking were feeling the revenue pinch still found at smoking bars. Rent seeking?

""It's too bad they didn't put as much effort into protecting their employees from smoking," grumbled Jeanne Weigum, executive director of the Association for Nonsmokers." Hmm, are the employees FORCED to work there? Is this the only job they can get? My guess would be that the tips they get from the smokers are far better than those at Waffle House.

"The Health Department this week vowed to begin cracking down on theater nights with fines of as much as $10,000." I suppose that the health department knows that "out of one hundred smokers, fewer than six will get lung cancer. . ."(Why People Hate Economists (and Why We Don't Care))It would seem the health department knows what is best for me better than I do and feels I cannot make my own choices, maybe like the impending environmentalism movement?

Will they ever make a law without loopholes? Due to spontaneous behavior, I seriously doubt it.

The article talks about how a recent smoking ban in Minnesota has a loophole that "contains an exception for performers in theatrical productions." So, bars are allowing "theatre performers" to smoke all night. The loophole, which we will speculate in a moment, was found by a political entrepreneur (actually a lawyer, but then who better?).

As we have discussed in class, a law passed by a citizen vote (democracy), like the one we have in the state of Colorado, is different from the law passed by the legislature in Minnesota. We should then look for who wanted the law passed in Minnesota. My guess would be those restaurants that have gone to no smoking were feeling the revenue pinch still found at smoking bars. Rent seeking?

""It's too bad they didn't put as much effort into protecting their employees from smoking," grumbled Jeanne Weigum, executive director of the Association for Nonsmokers." Hmm, are the employees FORCED to work there? Is this the only job they can get? My guess would be that the tips they get from the smokers are far better than those at Waffle House.

"The Health Department this week vowed to begin cracking down on theater nights with fines of as much as $10,000." I suppose that the health department knows that "out of one hundred smokers, fewer than six will get lung cancer. . ."(Why People Hate Economists (and Why We Don't Care))It would seem the health department knows what is best for me better than I do and feels I cannot make my own choices, maybe like the impending environmentalism movement?

Will they ever make a law without loopholes? Due to spontaneous behavior, I seriously doubt it.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)